Recognising IRD

There are lots of different types of IRD and lots of tests doctors can use to diagnose them

It looks like you are using an older version of Internet Explorer which is not supported. We advise that you update your browser to the latest version of Microsoft Edge, or consider using other browsers such as Chrome, Firefox or Safari.

There are lots of different types of IRD and lots of tests doctors can use to diagnose them

There are a range of different signs and symptoms that your child or loved one might experience, beyond problems with their vision. These vary because of the number of diseases that are included in the term inherited retinal dystrophy.

Some of the ocular signs to look out for that can suggest your child or loved one might have a problem with their vision and that can prompt a doctor to arrange further tests are:

In babies and young children

In older children and teenagers

In children and adolescents, signs of a potential issue with vision can show up in other ways:

Receiving a diagnosis for an IRD can be daunting for both you and your loved one, but knowing the process of a diagnosis is important in understanding your options.

There are two types of diagnosis for IRD: clinical diagnosis and genetic (or molecular) diagnosis.5

Clinical diagnosis

A clinical diagnosis is made based on the signs and symptoms on display as well as tests done in the doctor’s office. It is an assessment of whether a person has an IRD and, if so, what type. It might involve a number of different clinical tests carried out by a doctor or ophthalmologist. Some of these tests are outlined in more detail below.6

Genetic diagnosis

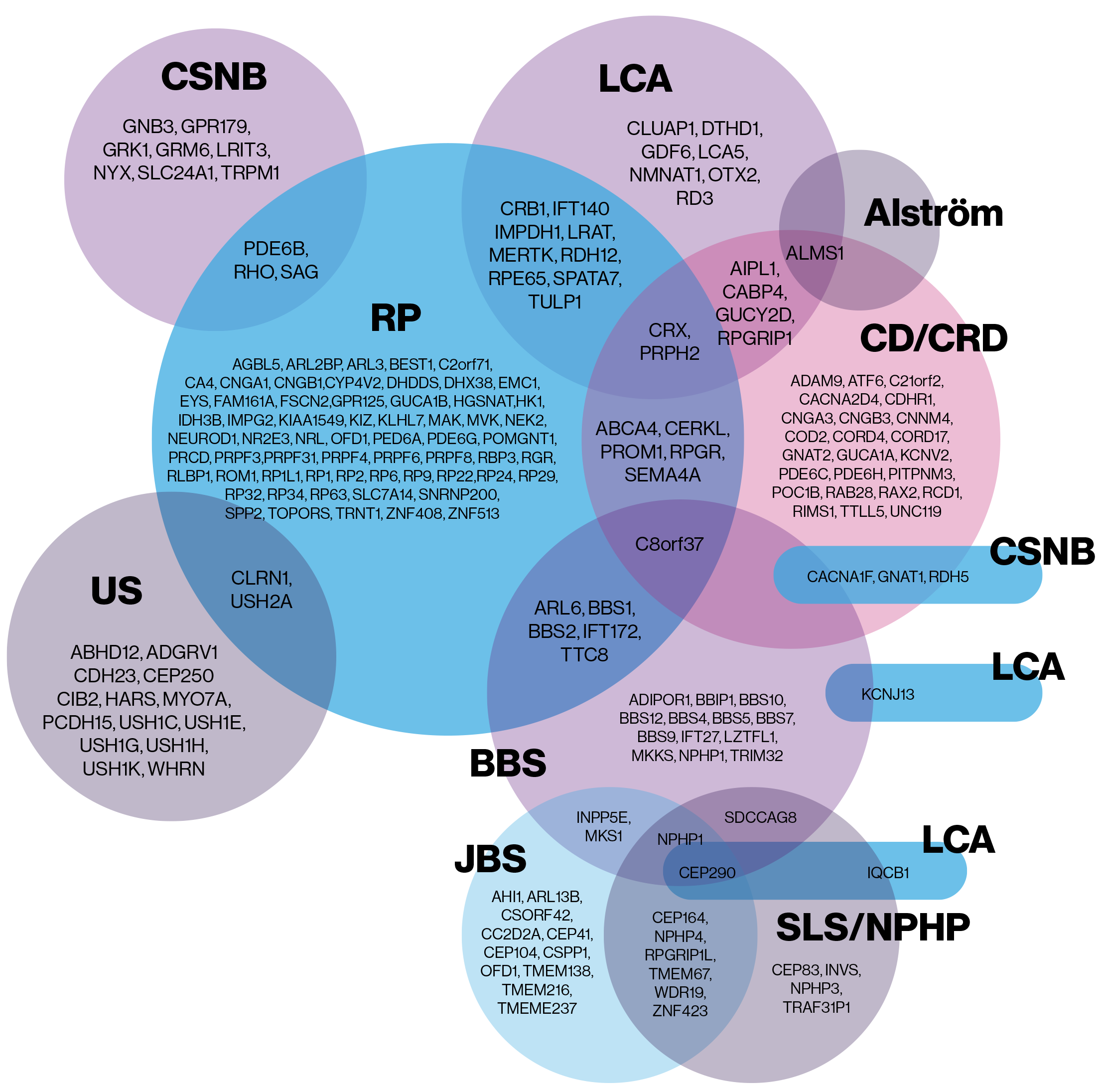

A genetic diagnosis is where genetic testing is used to find out exactly what gene mutation is causing an IRD. It’s used to validate and confirm the clinical diagnosis and find out exactly what is wrong. Not all of the mutations that cause IRD have been identified yet, but a large proportion have, and a genetic test should be able to tell you more and help inform the management of your child or loved one’s IRD.7,8

This video features a patient and her family discovering the symptoms and diagnosis of IRD. The family shares reasons for pursuing a genetic test and details their life after the diagnosis.

Beyond normal sight tests, there are a number of different tests that a doctor or ophthalmologist might carry out to identify IRD and get more information.

What is genetic testing?

A genetic test can be done after your child or loved one has been given an IRD diagnosis to provide more information about the mutation causing it and what their disease progression is likely to be. Genetic testing is usually done via a blood sample, and involves sequencing the genes in a laboratory and comparing them to mutations that are already known to relate to IRD.10 It’s done to give a more precise, genetic diagnosis of your condition and can help guide future management.

Why is genetic testing useful?

Genetic testing can help identify definitely if the patient has an IRD or not and, if so exactly what gene mutations are causing an IRD. This can help give a better idea of how the disease is likely to progress and can give the doctor more information to help guide disease management. A genetic diagnosis can also identify if your child or loved one might be a candidate for any ongoing or future clinical trials or approved treatments of IRD (see more here) and can help provide information that can guide further research into the treatment of different IRDs.11

As well as this, a genetic diagnosis helps to provide your child or loved one with reassurance about their condition, and give them important information about the likelihood of passing it on to any children they may have in the future.9

Getting referred for genetic testing

Your child or loved one’s ophthalmologist or doctor will usually want to make a full clinical diagnosis before proceeding to genetic testing. They may also want you to speak to a genetic counsellor before referring for genetic testing, as they can help you make sense of the results.9

References

_________________